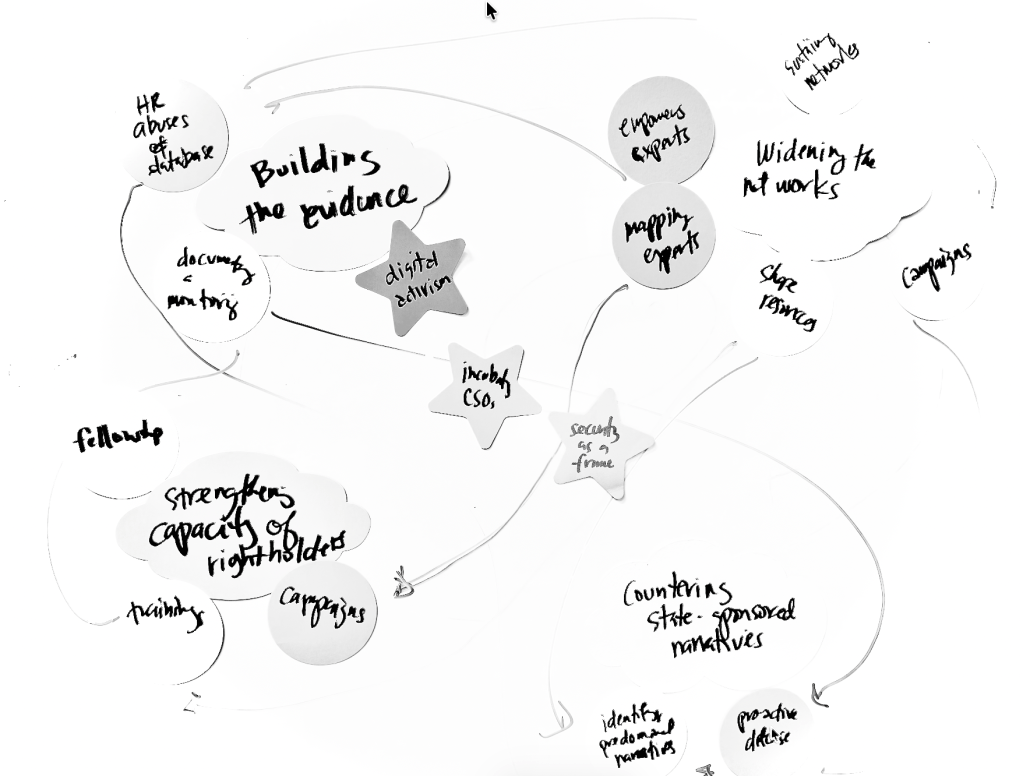

I helped two organisations in 2025 develop strategic plans and used systems thinking to better situate their plans within the complexity of the problems each organisation wanted to tackle. The realisations of both organisations converged on a few key themes – the process made them think more deeply about the problems they wanted to solve, explore new ideas and engage with stakeholders beyond the usual suspects, and make sense of some of the efforts they were undertaking that were outside the scope of “net-effect” impacts.

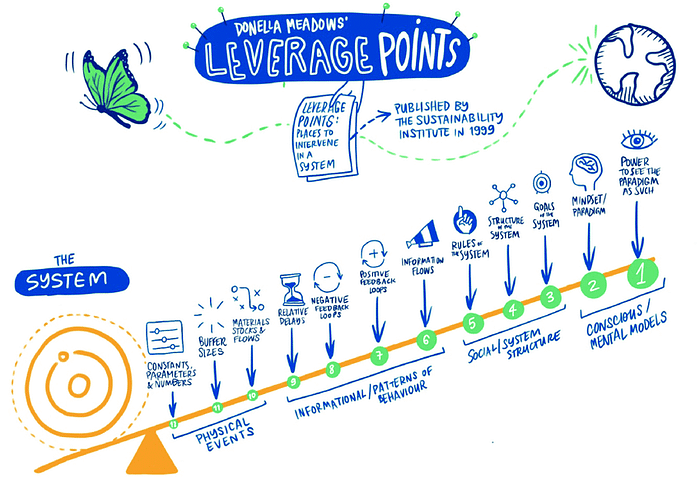

I thoroughly enjoyed the process, especially when the participants reconsidered the importance of identifying leverage points and the layers at which they can “intervene”; from parameters to mental models. But I am not writing about systems thinking in this post – there are so many excellent resources available from key thinkers in the field. I am writing more about the process of decision-making and how, for some reason, it resonates with the processes of sense-making and thinking in systems.

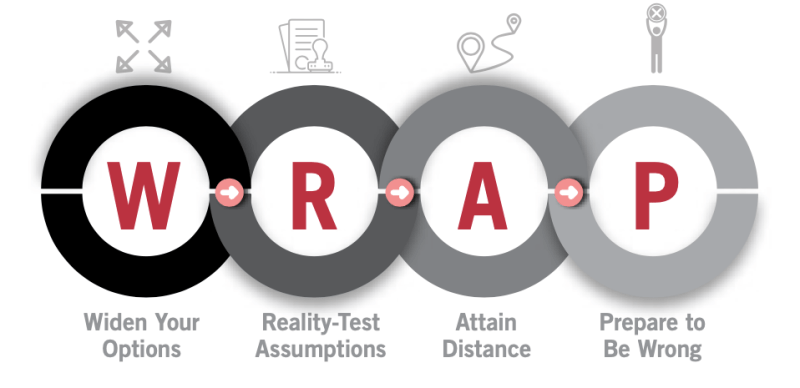

This month, I began my reading list with a re-read of the Heath brothers’ book “Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work”. I loved their work in “Switch” and “Made to Stick”, that when this book came out in 2013, I bought two, one for me and another for a friend who was then contemplating a big decision in his life. It got mixed reviews, but I did enjoy the writing, and the mnemonics that they use to describe their suggested methods of decision-making. It’s called WRAP (The visual below comes from the blogpost from Australian leadership coach Bruce Williams).

Widen Your Options

The strategic planning teams I worked with appreciated the systems mapping exercises we conducted, as they made them think beyond their usual areas of interest. In strategic planning exercises they have done in the past, the process starts with context analysis. When context analysis is not done well, it can result in what is normally described as “narrow framing” or “spotlighting”.

Systems mapping avoids this by asking organisations to create a systems map. While boundaries are defined, it makes organisations think beyond their immediate environment and avoid narrowly focusing their discussions on the kinds of problems they want to address. It makes them consider other issues relevant to their work (e.g. religious norms) that affect the issues they would like to address (e.g. household decision-making processes).

Reality-test your Assumptions

Creating change pathways will sometimes miss articulating important contextual and causal assumptions. For example, creating online campaigns is often hypothesised to increase awareness among targeted audiences. But there are several “causal jumps” occurring between this cause-and-effect narrative, including, that the targeted audience uses the chosen medium of the campaign, that the message is compelling enough to be read, and that the issue is important to them to trigger a reaction.

Systems mapping helps to particularise the progression of results and makes visible several of the assumptions that underpin the leverage points that planners will identify. This is crucial, especially for those that are theorised to lead to transformative results. For example, enacting freedom of information laws can be transformative in terms of accessing information, but this will not necessarily lead to concrete implementation. Systems mapping helps us to question our assumptions and avoid confirmation bias.

Attain Distance

The Heath brothers argue that short-term emotions and conflicting feelings get in the way of making useful decisions. Other authors contend that emotions are important for motivating action, not for making good decisions. Thus, these authors ask us to step back and approach the issue with a far-removed lens than the one we actually have.

Using systems thinking during strategic planning helps us ask how other actors within the system would approach the problem, or have approached it, given their motivations and interests. In systems thinking, there is an implicit recognition that we are not the only ones with a stake in the system – some elements align with our intent, while others do not. Thus, looking at the various actors in the system with different incentives and interests helped the groups I worked with adopt a more pragmatic and objective approach to the problems, or to the proposed solutions.

Prepare to be Wrong

There is really no room for overconfidence when we plan. A glaring fact in our planning sessions is our limitation, as individuals and as groups, to predict the future. Jumping to faulty conclusions infects several decision-makers, and sometimes they create narratives to save themselves from their poor decisions.

There is implicit humility when we do strategic planning using systems thinking. First, we acknowledge that our understanding is limited, so we try as much as possible to capture reality and our understanding of society through available evidence. Second, we avoid simplifying complex problems and refuse to describe the world in linear, reductionist terms. Third, we try as much as we can to uncover the underlying patterns and structures of the system and revisit our systems maps regularly, because we know that our understanding is temporal and the system evolves over time. It is remarkable that the teams I worked with last year have become more self-critical of their knowledge and tagged several items in their systems maps as items to explore further or verify.