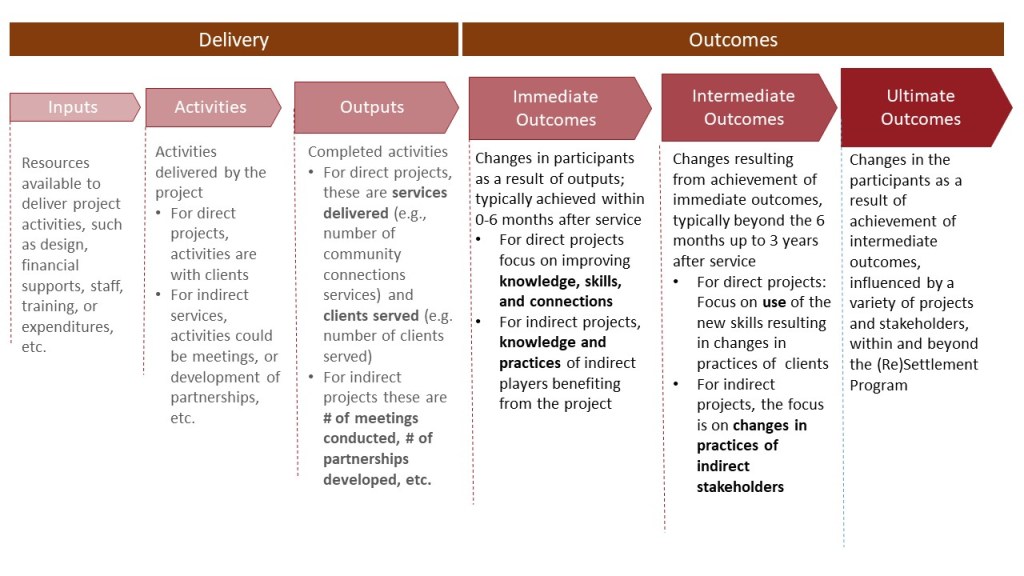

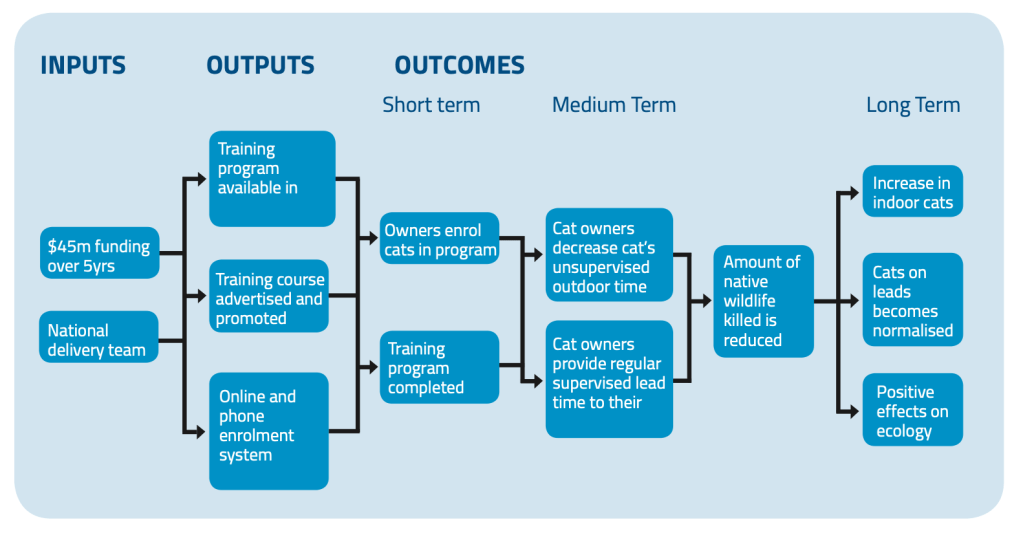

In international development programming, the phrase “outcomes” refers to the desired, measurable changes or benefits that result from a program or project as a consequence of outputs achieved. Some outcomes are considered immediate -those direct results of the production of outputs, while others are considered intermediate or ultimate, which can be likened to higher-order results. For example, in Canada’s development programming below, improvements in knowledge and skills are direct consequences of a training (hence, immediate), but the use of those knowledge and skills is at a different level of results (intermediate) as improvements in knowledge and skills do not necessarily result in a change in practice or behaviour.

In development projects funded by public (e.g. governments) and private (e.g. philanthropists) donors, project proponents or implementers are always asked – What results do you want to achieve? What outcomes do you seek? In a lot of cases, proponents are asked for a program logic, or a results framework (see below), where they will be required to describe in detail the results that they aim to achieve. This, I refer to as “intended outcomes” – or those planned results that implementers commit to achieving over the life of their programs or projects.

I contrast this to what development literature would describe as “unintended outcomes”. Unintended outcomes refer to positive or negative results that are a natural by-product of the complex systems in which an intervention is introduced. Unintended outcomes, in other contexts, are called side-effects, indirect results, or unplanned consequences, indicating a linearity of thinking and a simplistic articulation of what the world looks like. If you do this, then this happens: a direct causality between an intervention and an intended outcome.

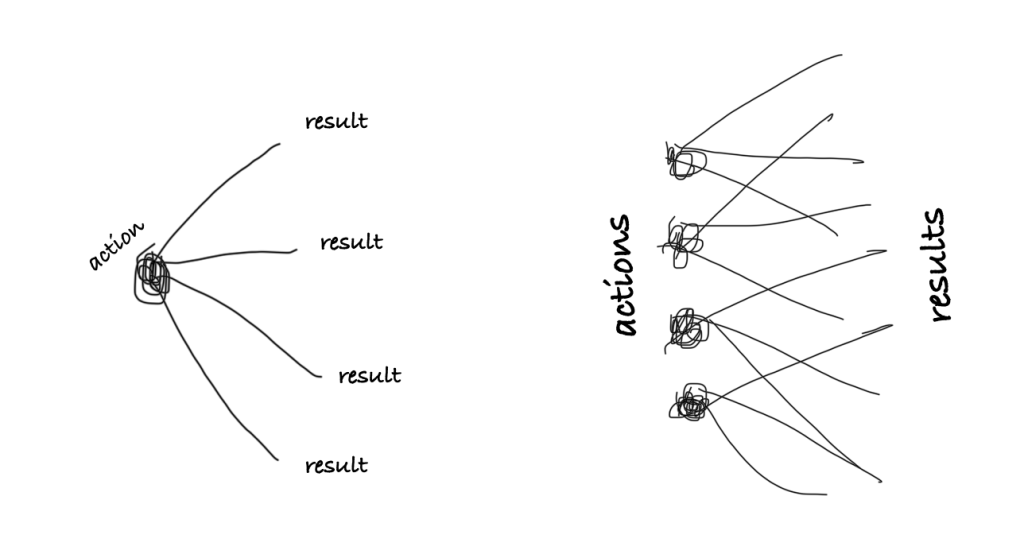

But we all know that this is not true. A trainee learning a new concept or skill is not just a result of training. It is a result of so many other factors – a clear mind because the mother-in-law took care of the kids and the house, a working public transport that departs and arrives on time, previous knowledge about the topic, fluency in using the language of instruction, and so many other things.

In the same way, our actions do not have a single effect. To say that one thing leads to another main result, and all others are just “unintended”, if not minor results, is indicative of the same linear and simplistic thinking. Training not only results in gaining knowledge and skills, but it can also lead to better relationships with co-trainees, insightful discussions with trainers that lead to collaborative projects, and increased commitment to a reform agenda. To say that all these attendant results are minor or unintended misses the point.

This phenomenon in development programming is what I call the tyranny of intended outcomes.

Intended outcomes become the very focus of project implementers and donors alike. Projects are conceived, funded, and executed in pursuit of measurable goals and quantifiable impacts. This is not bad, but when it becomes the sole guiding principle for development initiatives, it will sideline the richness, spontaneity, and unpredictability that define real change. Development projects then lose sight of responsiveness and learning, and lean more towards conformity, rigidity, and sometimes, unintended harm.

There are three things that I would like to emphasise in this discussion.

Firstly, unintended outcomes are often not truly unintended. The term is problematic because it ignores the fact that our actions can generate various, sometimes conflicting, effects. It also fails to recognise that results stem from multiple actions happening at the same time. Essentially, what we call unintended outcomes are all part of the wider consequences of carrying out a range of interventions.

Second, when we treat unintended outcomes as “surprise” results but do not incorporate them into the habits and ethics of regular monitoring, we then feel compelled to demonstrate success through the neat arithmetic of pre-set targets rather than the messy and iterative language typical of programme implementation. Our perspective becomes limited, and our narrative remains incomplete. When we fail to make the often invisible results visible, we miss the opportunity to tell the full story of what truly occurred. Consequently, we end up speaking only of half- or quarter-truths.

For example, our fascination with metrics might show an exponential increase in agricultural yield but neglect the depletion of soil and water quality. We may demonstrate how microfinance economically empowers many women but fail to reveal how decision-making has shifted within several households. When success is measured only against intended outcomes, these stories become invisible, and learning stagnates.

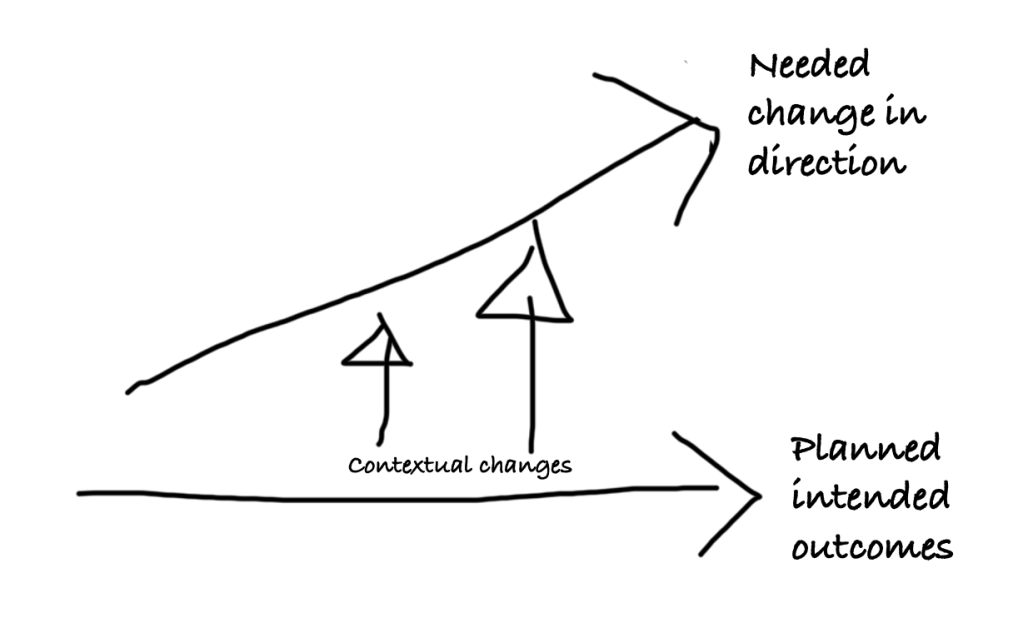

Finally, focusing too much on intended outcomes can strongly discourage agility and adaptability. As economic and political contexts evolve, project participant needs change, and local priorities emerge, programme flexibility is needed not only from programme managers but also from other stakeholders. Overemphasis on project logics may cause stakeholders to hesitate in pivoting – activities continue as planned even when there is a clear need to change course. In some cases, activities may become irrelevant or, worse, counterproductive.

Project logics, results framework, and theories of change are meant to be management tools that allow for flexibility and adaptation. The desire for change, planned three or five years ago, should not determine how implementers make their interventions relevant. Intended outcomes are the goal – if we focus too much on them during our journey, unaware of the constantly changing local realities, we miss the experience. We are making a significant trade-off with the true essence of development – humility, mutual discovery, and local adaptation.

Viewing results measurement from a systems perspective and allowing a more cohesive description of the journey of a development project is not about sacrificing ambition. It is more about recognising that change cannot be mapped with precision and that the world we are trying to change has a history built through a complex web of interwoven relations, and a delicate balance of intention and possibility.